_____________________________________![]() Oops, science is POWERFUL!

Oops, science is POWERFUL!

ENGL 390, 390H, and (sometimes) 398V Class Journal

_____________________________________

Entries by Marybeth Shea (1075)

Week 11: what shape will your review document take?

Monday! (link IS THERE!)

You have an ER Reviewing task due this evening. Help each other move forward. If you missed Friday's ER Writing Task, please read the email I sent via ELMS mail. Respond and you can do the awkward but helpful work around.

If you looked at all the resources last week, you saw a lemon on one of the slides. Why? Well, documents have shapes!

Here is the Research article slide set (Google Presentation) we looked at last week. We will also go back and look briefly at K. Barr's presentation on how ABT statements fit with research article sections.

By now, you have likely skimmed your article or -- at least -- the abstract. You may have also looked at the suggested reading grid given last week, too. Marked in purple, you may recall that you will work with three or four takeaways from this research article. In other words: Seek three or four points that you could use to place in the center portion of a:

- lemon-shaped document

- pear-shaped document

Naming of parts: Documents have beginnings, middles, and ends. For this work, think LEMON-shaped. Here is a good way to arrange your analysis:

Beginning: 1-3 paragraphs that prepare the reader to understand and trust the center portion of your analysis (three or four body paragraphs). Use a cognitive wedge strategy aka "lemon nipple." Think:

- Opening (see the seven strategies (Google doc based on RICE University's CAIN project -- you can combine them.)

- Version of an ABT statement

- Ethos of lead author (like Davis and/or Hocking, Moore)

- Definitions/descriptions or backgrounds, which is largely common knowledge.

Middle: 3-4 body paragraphs. Start with one paragraph per point BUT you may need to divide complex material into two shorter but connected (by transition) paragraph. These are your larger paragraphs. You MAY need to nest small definitions -- use the appositive technique -- near the material.

End: Taper off, with some useful information or thoughts for closing. For example, brief critique (this is hard and will NOT count against your work grade-wise), applications, further line of inquiry, implications for society. And, many find that the same ABT statement or a new one is another good way to close. Remember how you restate the thesis in five-paragraph essay or ECR?

Week 10: Assignment 3, the close one-article review

Warm and likely a spring storm today.

Let's start with some due dates:

- Tonight! Last ER Reviewing Task for the coffee cup memo. GET IN THERE.

- Friday, I open up the coffee cup parking lot and you have one week.

- Friday, I will also open up a short assignment for your article review, Assignment 3

- You will need the abstract of your desired piece.

- Number 3 means you have an article now or will have one by Friday. Must be peer reviewed article of your choice. For comp sci/data sci students, please email me because your field publishes differently than many expert disciplines.

- I will fill out the April to May ELMS calendar for Assignment 3. And, debut two ways to complete:

- Train A to complete early (close to the last day of class)

- Train B to complete midway through finals.

Now, on to more work thinking about transitions between paragraphs and even document sections. We have two metaphors for this. First up? muffin tin.

In the muffin tin metaphor, we chunk information into the tins, which is natural and good. We divide complex information to conquer the complexity. Doing this heaving cognitive lifting is necessary for analysis and even uses of the information. However, muffin tin "scoops" of information are largely the type of information that is joined by the conjunctive and. We have yet to introduction the powerful (also wakes up reader cognition) conjunctives of but (however) and or (contrast or choices or options). We have yet to introduce the power of therefore, where we create meaning and actions based on meaning. See the video below from Randy Olson.

One of Aristotle's canons for writing is ARRANGEMENT. The order and "chunking" of information matters very much for reader cognition and receptivity to what you write.

Now, the (Lego) train metaphor, where the cars are different, helping us think about and, but, or, and toward the end (caboose) of therefore.

Now, to the exciting and somewhat potty-mouthed Randy Olson, marine biologist, filmmaker, and science communication evangelist. (NOTE: Video fixed at 3:20, Monday)

Randy's work is the and, but, therefore framework, which we call ABT.

Let's think a bit about peer reviewed research articles and link this topic to ABT statements/framework:

- This google slide set about the research article.

- Keep a running grid on your reading. Copy this google doc to your drive. Reading IS essential to writing. Again, this is part of my case for labor grades. ABT statement is previewed here.

Happy Wednesday.

We will pick up links from Monday to

- consider the most common type of science/tech article

- hear more from Randy Olson the potty-mouth guru of science writing

- look at examples of ABT statements

- NEW to you: slide set of ten samples from a workshop at UMCP with Olson (environment discipline) PLUS a set of medical humanities ABT workshoping in a Google Doc.

- Keisha Barr, with Randy Olson, on the "narrative gym" frame of ABT and IMRAD work (7 sldies, highly visual)

Friday! Necessary rain, so my plant scientist/gardener heart rejoices.

Will be here, as per usual,

- 9-9:50

- 11-11:50.

(mini lesson: when do you use numbers and when do you use bullets? Numbers help with order matters.)

You have TWO -- count 'em, two -- ER Writing Tasks now live and "due tonight. Here is how to think about what is due for realz and what is due over a week (hint: parking lot metaphor):

- ER WRITING TASK for prewriting Assignment 3, the close review of your selected article

- ER WRITING TASK for a parking lot approach for Assignment 2, for a grade.

(Mini lesson: order matters or can matter in bullets. Note that I put your PRIORITY ER WRITING TASK first in the bulleted order; this suggests that this task takes priority over the "parking lot" task.)

Song of the day (what is the greener disposable hot beverage cup?):

More Kermit in our lives and way less (let's just say no amount is health for children and other living things) Pepe the frog.

Week 9! (8 was spring break): coffee cup nearly done; one article close review up next

Morning, returning Terps.

You have an Eli Review Reviewing Task due this evening. Help each other out! ASAP.

Let's gather up resources to chat about today and Wednesday. You have seen these before in this journal and as reposts in Eli Review Writing Task/Reviewing Tast prompts.

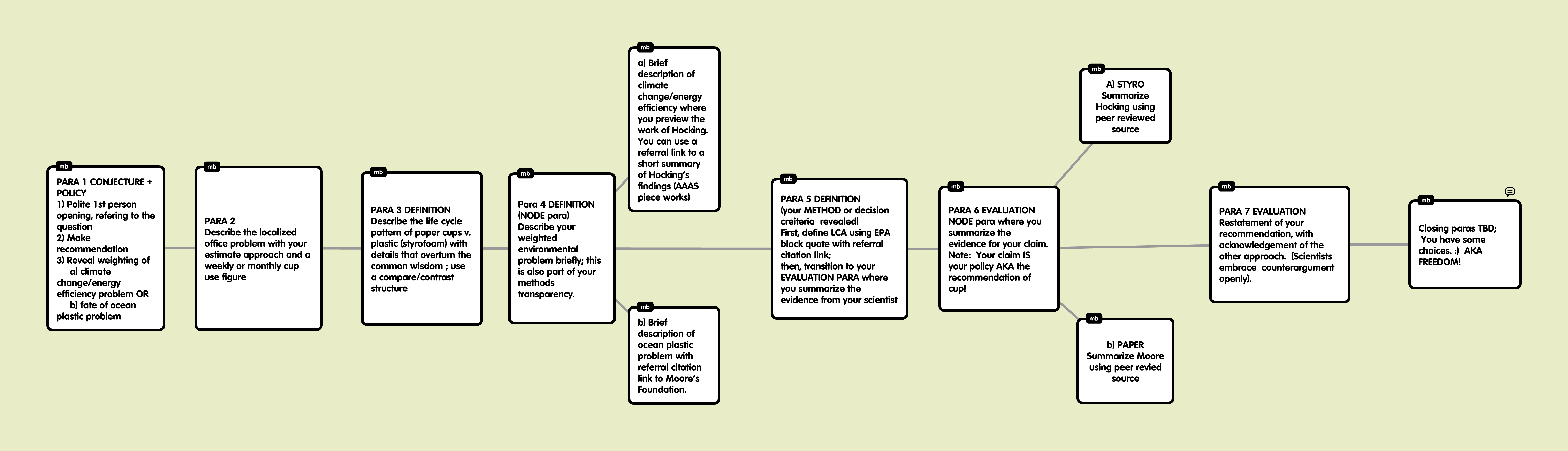

- Lime-green flow chart

- coffee cup round-up document (focused on free phrases, sentences, perhaps a bit of a paragraph or two; AKA mentoring text to propel writing forward).

- Here is a dummy text exhibit in Google docs using lorum ipsum about the coffee cup memo pattern.

NEW: Here are questions from last year in an interactive google doc.

Today, I will reflect on several topics/conundrums about wrapping this assignment up. We can also ANSWER YOUR QUESTIONS, too.

Mb topics:

- PARA 2 local and global problem description (stasis two of definition WITH the logos of numbers.

- PARA 1 (reveals frame, sets up for the punt paragraph of PARA 4 (a node paragraph)

- PARA 5 category of problem approach: life cycle analysis/cradle-to-grave (stasis two of definition; EPA is the accepted authority here, though the ethos is rapidly being diminished just now)

- PARA 7 restates your recommendation in PARA 1; then acknowledges the reasonableness of the other frame

Options (PARAS 7 and 8):

- offer a combined solution

- caution graciously about the limits of this framing and -- indeed -- the question

- suggest that the team research more carefully what others (including, perhaps the EU and the Netherlands) are doing.

- Offer to track the emerging health problems with microplastics, with focus on local watershed

- Note the incommensurability problem here

Now a few words about Assignment 3 and what sort of technical article you need from your field. Select an article to review I noted this in the syllabus. Details: Find a research results article published in a peer reviewed journal. You will read, analyze, and review this piece in the manner of a journal club. We imagine that at Leaf it to Us, we share knowledge with each other across our disciplines every Friday. We share an in-depth write up of the article after we present. We can assume that all will read/skim the article. However, the heavy intellectual lifting is on the presenter. Hints on how/where to find an article:

- are you reading an article for a class now? Select that and you learn for both classes (efficiency),

- did you read last semester for a class? Select one of those articles (cognitive),

- are you deeply interested in a topic and want to explore (interestingness).

Please have an article in mind by Friday.

Wednesday, all day. Half way through the week. We will continue to chat about the documents/content posted for Monday. Two small items here:

- You do NOT need to address specifically some of the nuanced aspects of this problematic context. You can simply follow the simplicity (relative!) of the lime-green flow chart. I give the others options because bright minds naturally linger on these other aspects. What I offer -- to those who want this -- ways to quickly and respectfully address them.

- two-prong solution (lift up cause of reusuables

- comment on how both problems require attention, simultaneously

- characterize the human but false "move" to figure out the worse problem (mention incommensurability, if you like)

- offer to lead a team to think more deeply on this work

- writing craft reminder: I do not want you to use empty subjects, namely there is/there are and it is/was

- related: do not use it in this document at all

- We will chat about the uselessness of it in so many exacting contexts (all of professional communication)

AM POSTING ON THURSDAY!

Happy Friday. You have an Eli Review WRITING TASK due this evening. Be on time; this is your LAST chance to enter a place to give and recieve feedback.

I will open a Parking Lot in Eli Review, as a WRITING TASK, to submit your Assignment 2 for a grade. You have a week to turn in.

Drop by between

- 9-9:50 OR

- 11-11:50

To chat.

Resources for you as we wrap up the Coffee Cup Memo aka Assignment 2.

- Lime-green flow chart;

- coffee cup round-up document (focused on free phrases, sentences, perhaps a bit of a paragraph or two; AKA mentoring text to propel writing forward);

- Here is a dummy text exhibit in Google docs using lorum ipsum about the coffee cup memo pattern;

- questions from last year in an interactive google doc; and

- Checklist for Assignment 2, the coffee cup memo.

- NEW: 8 minute voice over/video walking you through items 1-5, which I discussed with you on Monday and Wednesday. This synthesis video covers that material for you in a new modality. Hope this helps you (I used Screencastify).

See you Friday, should you wish to visit me. Let me know if this new option of synthesis video helps you.

Week 7: coffee cup, spring break and letting document rest a bit

Good morning in the new time regime of Spring Forward.

Cognitive frame that is really hard but totally important to human beings who must work through complexity. incommensurability. Here is long entry from the Stanford Library of Philosophy (online). TLDR?

- Some concepts, methods, frames, social problems as well as policy decisions cannot be compared directly. Why? They lack a common measure. Some of the is math-focused but qualitative factors can be part of incommensurability, too.

- Consider apples and oranges, that old metaphor.

Why are we talking about incommensurability? Simply put: this memo is really hard to think about because our first instinct is figure out WHICH environmental problem is worse and then recommend a cup choice that addresses this problem. Makes sense in the mind. Yet, the world is not in our mind. The world is wild and complex and resists analysis all the time. This means the confusion and frustration you feel is human.

Knowing that some problems resist common measure helps us make sense of the non sensible world.

Side trip in philosophy of how science works: Have you heard of paradigm shift to describe how scientists build knowledge (claim and counter claim. Thomas Kuhn, philosopher of science, claims science process reveals that some discussions/arguments about competing paradigms fails to "make complete contact with each other’s views." This means (apples and oranges) that those in the "conversation" are always talking at least slightly at cross-purposes.

Kuhn calls the collective causes of this communication failures incommensurability. Here are some examples:

- the Newtonian physics paradigm is incommensurable with its Cartesian and Aristotelian predecessors in physics;

- Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier’s paradigm is incommensurable with that of Joseph Priestley’s in chemistry; and

- God's action as designer conflicts with Darwin's central understanding of evolution condenses into natural selection.

UPDATE today at 9:33 AM. After quick conversation with JK, I edited these passages to make sure that

the frame fits the cup.

Thank you, JK.

For us, we cannot compare directly the gravity of climate change with the fate of aquatic plastic. Therefore, in our memo we must lead with these sorts of framing statements:

In my analysis of hot beverage cups and environmental footprint, I weight climate change more heavily than ocean plastic. Therefore, this frame is a central assumption in this short problem-solution report. I recommend Styrofoam cups for their lower energy profile that that of paper cups.

You can also hint at how you will address this problem with qualifications in your recommendation at the end of this short memo.

Later in this short recommendation memo, I will address this conceptual framing limitation and speak briefly about how framing this problem as one of ocean plastic leads to another recommendation: paper cuups.

Comment on the above: If you chose this frame, you are TEAM STYROFOAM. In contrast, It you weight aquatic plastic as the central frame (TEAM PAPER), then your sentences look like this:

In my analysis of hot beverage cups and environmental footprint, I weight the fate of ocean plastic more heavily than climate change; this frame is a central assumption in my short problem-solution report in favor of paper cups.

Later in this short report, I will address this conceptual framing limitation and speak briefly about how framing this problem as one of climate change would lead to Styrofoam cups as the more environmentally sensitive cup,

Writing craft/collaboration note: you may use these sentences in your work as is or modify them as you wish. Remember that most workplace writing is collaborative. And, I am a coach-style supervisor. Additional comment: mentor texts are a good way to learn. A sentence is a text, therefore a mentoring passage. We learn by imitation of good models.

Coffee, tea, hot chocolate culture varies. Also added between the 9am and 11am sections? A visual about hot beverage culture, meaning that what if we drank hot beverages sitting down, with a ritual, and perhaps company rather than clutching a "venti". What kind of cup would Murial use?

Wednesday! The lovely weather continues. We have a grab bag of skills that will help you with the next draft (iteration) of your coffee cup memo. First up, let's think of achieving "flow" or cohesion in your memo. You want the reader to experience a unified, well-staged (arrangement). Because this memo leaps across a highly complex topic, we need flow to help our reader make the leaps with us. The overarching writing skill is the skillful use of transitions.

Find your LCA paragraph (PARA 5 in flow chart) that defines/describes this environmental technique (EPA source). Think of this paragraph as your PIVOT point in the memo. You are moving from description to set up the problem to analysis. LCA is the primary technique. How do you go from this pivot paragraph to the research of Moore (TEAM PAPER) or the research of Hocking (TEAM STYRO)? -->

Having defined LCA, let's look now at Martin Hocking's work on . . . (or, insert Charles Moore)

As you can see, Hocking's work is, essentially, an LCA on disposable hot beverage cups.

Moore's work focused primarily on the end phase of the LCA. Here, the key idea noted earlier about how "leaky" both disposal and recycling systems are. Essentially, we do not landfill and recycle near as much of both cup materials that we think; hence, we experience now a critical volume of aquatic plastic.

You can use these transitional passages as you begin the hardest paragraphs yet: summarizing the work of the researcher's peer reviewed analysis.

Establishing ethos of the researcher (early in PARA 6, which is a node para):

Moore, an oceanographer and now advocate regarding the problem of aquatic plastic, published in [X} journal, with several co-authors. This [YEAR] research article is one of the first descriptions of the extent of this emerging ecological and health problem.

Hocking published two experimental analyses comparing the energetics of paper and Styrofoam cups. published in the early 90s, Hocking's work is -- to date -- the only rigorous peer-reviewed analysis. Hocking, a materials chemist who died not long ago.....

When referral links are a punt: You need to develop a brief paragraph (PARA 4, also a node para) about the environmental problem you weight, using one or two logos of numbers to establish the seriousness of the problem. Here is language that might use or adapt-->

Climate change is widely understood by scientists to pose an existential threat....Estimates of temperature increases....Should you need more information on climate change and energy efficiency, see this helpful and brief and authoritative summary at [lin] which summarizes the science-based work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). CAUTION about size of PDF.

My short analysis (short analysis, first-cut look, quick-and-dirty examination), relies of the frame of aquatic plastic. Interestingly, the same scientist whose work I will summarize is also the scientist who discovred this problem. You can read about this work briefly at [link] and [link] Both of these non profit groups were founded by Moore. The volume of plastic in one large Pacific garbage paper approaches the size of Texa....

Why do I call this punting? You are not diverting your prose or the reader's attention to a full treatment of climate change nor aquatic plastic. You give a numbers-based detail or two, then let Jane go to authoritative sources if she needs to. Punt! With courtesy for the reader.

I use punt since more people are familiar with this idea. However, I prefer the baseball action of bunt. Brief definition video for your enjoyment, staring Mickey Mantle.

Here

- 9-9:50

- 11-11:50

I IMPLORE you to get this latest round of ER Writing Task IN TONIGHT. Yet, I do have a work around as an absolute firm edge of deadline at Sunday Noon. Then, I make a new ER Reviewing Task and open this over the break for THOSE WHO WANT TO WORK thusly.

Take care in time of rest and relaxation.

Might I caution you about St. Patrick's day? The fun can go quickly into fearsome troubles. I do enjoy many types of adult beverages but am always shocked at the excell on a saint's day, the one of my country of origin. Newer research shows that St. Patrick's day for some is the gateway to binge drinking, a very serious problem for individuals, people who love them, and society writ large.

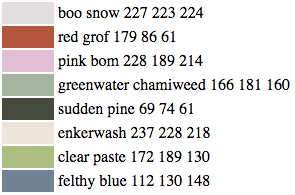

For fun -- after the sober PSA above -- read about AI and new paint colors. Janelle Shane combined color databases from paint companies along with names; then, she asked the "magic machine" to offer new paint colors with names. Imagine that you are at a surreal Home Depot paint chip display. Fun times. Lots of greens to contemplate.

If you come to class today, I will show you my Janelle Shane "Sudden Pine" tee-shirt. All the cool nerds either have one or want one or admire the swag.

Week 6: March is coffee cup recommendation month

Housekeeping:

- You have an ER Writing Task due by Friday. Turn in your rain garden memo for a grade (email me).

- NO ER Reviewing Task today (because you turn in your document to the "Parking Lot" for a grade.

- Knitting up from Friday:

- Did you look at what I posted re AI and Stasis theory? Skim is fine. I highly recommend listening to the "fake" pod cast.

- Couple of items to discuss briefly:

- What are hanging indents and why do we care?

- What does embedding a link mean.

On to the policy memo (we use ALL the stasis steps in this document-->

Source/citation comment: This time, we WILL USE peer-reviewed sources for two primary researchers: Marine biologist Charles Moore's work (if you plan to recommend paper cups) and for materials chemist Martin Hocking's work (recommending Styrofoam cups).

You will also use web-available summary documents as referral citations in several places.. Recall that we do not want our audience to hit a payway.

- Use the library research databases to find one peer reviewed source for each expert.

- Consider looking at environmental science and technology categories for Hocking. The two articles I am thinking of are circa 1991 and 1994.

- Consider marine biology or ocean science categories for Moore.

- For the open access sources, search the web for

- Charles Moore's foundation.

- A summary of Hockings' work at a major science publication.

- Use Wikipedia for a working sense of what life cycle assessment/life cycle analysis is. We will discuss in class how to use Wikipedia as a citation that both buids our ethos and is helpful to the busy reader.

- US AI and take notes, as we did for the prewriting activity (invention) for the rain garden memo.

This arrangment approach below can help us, too. Apologies for the large size file nested here.

Does this visualized arrangement of our thinking help? Here is a rough cut at how a flow chart would make the NODE paragraph choices clearer. What do you think? I saved this as a PNG file so this is scalable. You can download the image and look at this in an image viewer. I tried Popplet at the advice of JP Dickerson, in Computer Science.

Writing craft lesson that relies on cognitive awareness about how people read, think, parse meaning from writing: empty subjects. What are they? Perfectly usable subjects in sentences that can introduce confusion for readers. Try to avoid these constructions. Resources for you:

- Empty subjects (there is/are; it) This short web exhibit is chock-full of examples.

- Another name is dummy subjects (also web exhibit)

DO NOT USE THESE PLACEHOLDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN YOUR MEMO.

I will open up the ER Writing Task on Tuesday, close to noon. And, as usual, alert you in ELMS via mail and calendar.

HINT: pick a side. research as described above, both recommendations are justifiable by science. You can/will close with your critique of the question as well as the importance of reusuable cups.

For fun--> (use Google image search to leadn more, if you like.

Tis Wednesday -- all day -- Looks to be blustery and raining all afternoon. Items for today all toward the Friday ER Writing Task. You MUST pick a side. Now.

- TEAM STYRO: that relies on Martin Hocking's peer reviewed work on life cycle analysis of paper v. Styrofoam.

- TEAM PAPER: that relies on Charles Moore's peer reviewed work on fate/size of ocean garbage patches.

Free phrases and sentences (mentoring you! Here are some helpers, primarily focused on sentences you can use, whole cloth or modified, with some attention pair to paragraph options: coffee cup round-up document (Google, several pages capturing items from this Class Journal). Cute Hello Kitty to help you there. Why not? I got your attention, didn't I?

A few pearls for you in the "heavy compost" of what AI might give you about this complex topic. BOTH TEAMS should read these open access links, which you may want to mine for some referral links in your final memo-->

- this short letter in Nature by Hocking.

- Explore by clicking and skimming the Charles Moore Foundation website. His earlier foundation also is worthy: Algalita Foundation.

We will knit up stitches from Monday about empty subjects. Have you had enough visual metaphors today yet? Metaphors and visual references aid in memory.

Finally, we have one punctuation lesson, using a bunny graphic (Spring and Easter, y'all).

Writing craft lesson: What is an appositive? A bit of information you insert in between the subject and the verb. You need commas or other sorts of punctuation to set this off. This image of bunny paws can help you remember to do this:

Some bunny body parts (think morphology or form) fit three sets of punctuation: commas, parentheses, dashes. I will demonstrate in class.

Happy Friday!

Please listen to or view this under 3-min. YouTube by Bill Hart-Davidson, a founder of Eli Review. He also mentored me. Sadly, Bill died in 2024, rather suddenly. Here is a lovely Linked In post by N.C, regarding Bill. You may enjoy also the comment string of people who also loved and knew him, with many benefiting from his teaching innovation. I am still very sad.

Comment (always be learning): I had not thought of Linked In as a platform/genre for heartfelt condolences. We make new places to do ancient things, including to make (I use this intentionally) eulogies and sing (also intentionally) hymns of encomia. Indeed, this genre was well known to Aristotle: "encomium (G for eulogy, literally "good words") identifies an oratorical (spoken) genre in which a person, event, or thing is praised. In Aristotle's Rhetoric, the encomium is included under "epideictic oratory," which means instructional speech. The object of the speech is worthy of renown, study, and imitation.

Be like Bill. I think about this while using ER with students.

Can you see the defining and describing "rhetorical moves" (think chess, football, dance, etc.) in this coffee cup memo?

By the way, the document spoken above shares features of our coffee cup memo: writing for decisionmakers.

Your tasks:

- BE ON TIME TONIGHT FOR EACH OTHER in the ER WRITING TASK for Assignment 2. coffee cup memo.

- TURN IN Assignment 1 (rain garden) to ER WRITING TASK/PARKING LOT.

If you have to choose because some life happened, including exhaustion, please prioritize helping each other in the FIRST task (note, I used NUMBERS to order these tasks because order (priority) matters. Then, email early Saturday morning with a plan about when you will turn in Assignment 1.

If you attend today, I will show-and-tell two bits of swag from Janelle Shane and her AI Weirdness blog. You may remember her from the first week when I asked you to explore her droll use cases of AI.

See you between 9-9:50 and/or 11-11:50.